Public Action Against Mindless Theft and waste of state resources

The situation in the country remains so grave and dire that the official Auditor General’s report for 2015 found that just 1% of Kenya government spending and a quarter of the entire 1.6 trillion shillings budget was properly accounted for. Current reports indicate that Kenya loses approximately 600Billion shillings out of its annual budget of 2 trillion (close to 30%) through wanton theft and waste. Imagine what this amount could do in supporting health care for the poor, provision of quality basic education, clean water or employment for our youth?

Specifically, the Kenyan CSOs note with concern the following systemic and vicious failures of the political establishments, both at the national and county levels: That as noted by John Githongo, a prominent anti-corruption crusader, “corruption in Kenya has deepened and widened since President Uhuru Kenyatta came to power in 2013”.

- Mega scams such as the National Youth Service Saga, “Chicken Gate” Scandal; land grabbing; flawed tendering in the Multi-Billion Standard Gauge Railway; Misappropriation of devolved funds and current Afya House Scandal in the Ministry of Health among others remain unsolved. That majority of those adversely mentioned in the above scams are either close associates or relatives of senior state/public officers thus deepening vested interests and political complicity.

- That the institutions mandated to provide leadership in the fight against corruption have terribly failed to live up to the Kenyan public expectation; from the presidency, Judiciary, Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, office of the Director of Public Prosecution, Office of the Attorney General.

- That the president has failed to demonstrate genuine, bold and effective political will and leadership to combat corruption over the years. His admission of inability to battle graft in a recent state house anti-corruption summit sums it all.

- That the judiciary has failed to put in places mechanisms to expedite corruption related cases. As a result such cases take too long in courts. This has delayed justice and only encouraged corruption to thrive.

- That the Ethics and Anti-corruption Commission has failed to effectively and independently deliver on its key mandate; law enforcement, investigation and corruption prevention in the discharge of its functions. This has rendered the institution a friendly environment for the corrupt. In fact on many occasions the EACC has sanitized the corrupt.

- That most of the alleged grand corruption prime suspects have been exonerated through a sham process while those who have not been exonerated have not been prosecuted either but remain free to enjoy their loot.

- That most of the state/public officers who have declared their wealth have done so in private, thus without adequate public disclosure. This is a precedence set by the presidency hence incapacitating the public to hold both state and public officers accountable for their wealth.

- That the government has failed to demonstrate greater transparency in procurement processes by not publicizing information on tender analysis, detailed contractor profiles including list of directors, engagement contracts, project implementation plans, bills of quantities and other related information.

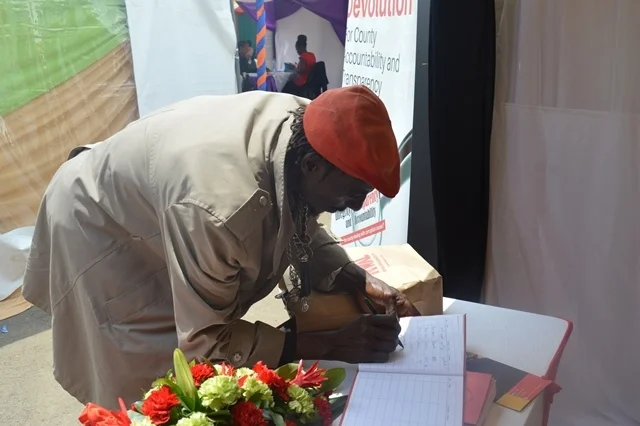

It’s in response to the president’s admission of helplessness, his inability to act, and the failure by the different state agencies to admit responsibility in the midst of wanton theft of state resources, that the Kenyan Civil Society is calling a national mass demonstration to demand for urgent and systematic actions against mega corruption in Kenya.

- The demonstration will take place on Thursday (03/11/2016) from freedom corner and will end with a submission of a petition with a Demand List to the president.

- The Demand List will capture the practical actions that the President should implement in line with his legal and political mandate and obligations.

- We therefore call upon the public and the media to turn up for the demonstration. We also request members of the public to come dressed in red and carry a whistle and the Kenyan flag.

We have planned sustained political actions to ensure zero tolerance to and increased accountability for public theft in Kenya.

Press Statement on the break-in into the home of Human Rights defender Mr. Khelef Khalifa

The Kenya Police Service should promptly, thoroughly, and transparently investigate the break-in into the home of the Chairperson of the Board of Directors of Muslim for Human Rights (MUHURI), Mr. Khelef Khalifa’s whose house’s was broken into at 4 am on 25 October 2016, in Mombasa County.

Loading...

Loading...

South Africa: Continent Wide Outcry at ICC Withdrawal

Victims’ Advocates Urge Reconsideration, Support for Court

(Johannesburg, October 22, 2016) – South Africa’s announced withdrawal from the International Criminal Court (ICC) is a slap in the face for victims of the most serious crimes and should be reconsidered, African groups and international organizations with a presence in Africa said today.

The groups urged other African countries to affirm their commitment to the ICC, the only court of last resort to which victims seeking justice for mass atrocities can turn.

“South Africa’s intended withdrawal from the ICC represents a devastating blow for victims of international crimes across Africa,” said Mossaad Mohamed Ali of the African Center for Justice and Peace Studies. “As South Africa is one of the founding members of the court, its announcement sends the wrong message to victims that Africa’s leaders do not support their quest for justice.”

South Africa publicly announced on October 21, 2016, that it has notified the United Nations secretary-general of its intent to withdraw from the ICC. However, there are significant questions as to whether South Africa abided by its domestic law in withdrawing without approval of its own parliament, the groups said.

“South Africa’s purported withdrawal – without parliamentary approval or public debate – is a direct affront to decades of progress in the global fight against impunity,” said Stella Ndirangu of International Commission of Jurists-Kenya. “We call on the South African government to reconsider its rash action and for other states in Africa and around the world to affirm their support for the ICC.”

“We do not believe that this attempt to withdraw from the ICC is constitutional and it is a digression from the gains made by South Africa in promoting human rights on the continent,” said Jemima Njeri of the Institute for Security Studies’ International Crime in Africa Program. “The South African government is sending a signal that it is oblivious to victims of gross crimes globally.”

South Africa’s announcement that it will withdraw from the ICC comes after the country’s court of appeal concluded the government violated its international and domestic legal obligations in not arresting ICC fugitive Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in June 2015, when he visited South Africa. A government appeal was pending, but on October 21, 2016, the government indicated that it has withdrawn the appeal.

“The decision by Pretoria to withdraw from the Rome Statute is a response to a domestic political situation,” said George Kegoro ofthe Kenya Human Rights Commission. “Impervious to the country’s political history and the significance of the ICC to African victims and general citizenry, the South African leadership is marching the country to a legal wilderness, where South Africa will be accountable for nothing.”

South Africa is the first country to notify the UN secretary-general of withdrawal from the ICC. Burundi recently passed a law on ICC withdrawal but has not submitted notification with the UN secretary-general as required to trigger the process of withdrawal.

The ICC is meant to act as a court of last resort, stepping in only when national courts cannot or will not prosecute some of the most serious international crimes.

Since 2009, the ICC has faced a backlash from a vocal minority of African leaders alleging that the court is unfairly targeting Africa. While all of the ICC’s investigations to date – with the exception of Georgia – have been in Africa, the majority have been initiated at the request of an African government: Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, and Uganda.

The situations in Libya and Darfur were referred by the UN Security Council. Kenya is the only African situation in which the government or Security Council did not make a request to the ICC regarding investigation.

At the same time, there is an uneven landscape. A number of powerful countries and their allies have been able to avoid the reach of the ICC, and of justice more generally. The ICC is constrained in reaching these countries because they are not parties to the ICC and because they or their allies on the Security Council have used the veto to block referral to the ICC of situations desperately in need of justice, including Syria.

The African Union (AU) has been a source of attacks on the ICC and in January 2016, it set up a committee to explore a strategy for ICC withdrawal. Many African governments continue to support the court, but have too often been silent in the face of attacks on it. Support has included cooperation with investigations and the referral of new situations to the court. Mali referred the crimes committed in its country in 2012, and Gabon referred crimes committed in its country in September 2016.

In July, during the AU summit, several African ICC members – Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Senegal, and Tunisia – took an important step in joining Botswana, a vocal ICC supporter, to expressly oppose an AU call for ICC withdrawal. Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Senegal also entered reservations to the July summit decision. Since 2009, activists across Africa have joined with international groups to call for African governments to support and strengthen the ICC, instead of undermining it.

“Now, more than ever, countries that believe in the rights of victims should affirm their support for the ICC,” said Oby Nwankwo of the Nigeria’s national Coalition for the ICC. “We should hear from Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Central African Republic, among many others, on the importance of the ICC in Africa and globally.”

For more information, please contact:

In Banjul, for Human Rights Watch, Daniel Bekele (English): +1-917-385-3878; or bekeled@hrw.org

In Abuja, for Nigerian Coalition for the International Criminal Court, Chino Edmund Obiagwu (English): +234-0703-000-0014; or +234-012-802-009; or +234-0803-691-3264 (mobile); orobiagwu@ledapnigeria.org

In Accra, for Ghana Center for Democratic Development, Franklin Oduro (English): +233-249-77-7788 (mobile); orf.oduro@cddgh.org

In Banjul, for Burundi Coalition for the ICC, Lambert Nigarura (French): +220-271-2084; or +257-71-741-127; or +250-78-377-0959; or nigarlambert@gmail.com

In Freetown, for Center for Accountability and the Rule of Law-Sierra Leone, Ibrahim Tommy (English): +232-76-365-499; or ibrahim.tommy@gmail.com

In Johannesburg, for International Commission of Jurists and Fédération Internationale pour les Droits de l’Homme, Arnold Tsunga (English): +27-716-405-926 (mobile); orarnold.tsunga@icj.org

In Johannesburg, for Human Rights Watch, Dewa Mavhinga (English): +27-73-5211-813 (mobile); or mavhind@hrw.org

In Johannesburg, for Southern Africa Litigation Centre, Angela Mudukuti (English): +27-767-623-869; or AngelaM@salc.org.za

In Lilongwe, for Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation, Fletcher Simwaka (English): +265-999-285-604 (mobile); orflesimwaka@yahoo.com

In New York, for Coalition for the ICC, Steve Lamony (English): +1-646-465-8514; or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it." target="_blank">lamony@coalitionfortheicc.

In New York, for Human Rights Watch, Elise Keppler (English): +1-212-216-1249 (office); or +1-917-687-8576 (mobile); orkepplee@hrw.org

In Nairobi, for Kenya section of the International Commission of Jurists, Stella Ndirangu (English): +254-7222-336-399; or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it." target="_blank">stella.ndirangu@icj-kenya.

In Nairobi, for the Kenya Human Rights Commission, Andrew Songa (English): +254-722-264497 (mobile); or Asonga@khrc.or.ke

In Pretoria, for the International Crime in Africa Programme, Institute for Security Studies, Jemima Njeri (English): +27-832-346-566; or +27-123-469-500; or jnjeri@issafrica.org

The following organizations that are active in an informal group that promotes justice for serious crimes endorsed this release (additional endorsements will be updated online):

African Center for Justice and Peace Studies (Uganda)

Africa Legal Aid

Burundi Coalition for the International Criminal Court

Centre for Accountability and Rule of Law–Sierra Leone

Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation (Malawi)

Center for Democratic Development (Ghana)

Civil Resource Development and Documentation Centre (Nigeria)

Coalition for Justice and Accountability (Sierra Leone)

Coalition for the International Criminal Court

DefendDefenders (Uganda)

Federation Internationale des Droits de l’Homme

Foundation for Human Rights Initiative

Human Rights Watch

International Commission of Jurists

International Commission of Jurists–Kenya

International Crime in Africa Program at the Institute for Security Studies (South Africa)

Kenya Human Rights Commission

Kenyans for Peace, Truth, and Justice

Legal Defence and Assistance Project (Nigeria)

Ligue pour la Paix, les Droits de l’Homme et la Justice (Democratic Republic of Congo)

Nigerian Coalition for the International Criminal Court

Parliamentarians for Global Action

Southern Africa Litigation Centre (South Africa)

Vision Sociale ASBL (Democratic Republic of Congo)

Electoral Reform for Lasting Peace in Kenya

Chacha opines that there have been no repercussions for those involved in electoral malpractices for these reasons. In such a situation according to Chacha, it is inevitable that leaders continue to threaten, buy, or trick their way into power. Further without monitoring the electoral process, it is impossible to identify and therefore address any challenges. But all is not lost. With the support of Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC), Chacha decided to change the situation.

Reports from 57 human rights’ election monitors such as Chacha highlight misuse of funds in several sectors. State resources for electioneering were noted to have been misused which led to the Commission of Administrative Justice (CAJ), to confirm that public servants who used or misused public resources for the benefit of their party were culpable of abusing their powers. These reports also influenced the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) to issue a legal notice warning state officers against using government resources in campaigns. The IEBC gave all public officers contesting in the 2013 general election two weeks to declare the public facilities at their disposal by virtue of their office. The IEBC warned those that did not comply that they would face fine or imprisonment. Chacha, in his small way, set the pace for an election that prohibited misuses of public resources among other things, with support from CAJ and IEBC.

For the first time, there were repercussions for those involved in electoral malpractices thanks to 57 human rights election monitors like Chacha who operated in 20 counties across Kenya. For instance, those accused of voter bribery and people attempting to vote twice were arrested. Politicians then realised that there was a watchdog and this changed their behaviour. This could be a reason why youth were not incited as frequently as done in the past.

In-depth monitoring of elections also led to better preparedness for the actual elections, for example, there were adequate materials at polling stations, biometric voter identification devices etc. Additionally, Electronic transmission of results functioned better and there were prior consultations between civil society and the IEBC. This is evidence that monitors, such as Chacha, can change the status quo and mitigate electoral related problems.

Chacha was empowered to take charge in this process as he was trained in election monitoring tools, election related law, international instruments and treaties on civil and political rights by KHRC. As a community-based Human Rights election monitor he utilized the agreed monitoring tools to record human rights violations related to party nominations, electoral campaigns and voting. He conducted this in a data driven process attending politically motivated events (rallies, funerals, office launches, church meetings and fundraising events) and systematically monitored the media. He made records of all electoral processes before, during and after the elections. Community-based Human Rights monitors submitted over 3,000 reports with photos, audio and visual recordings, to the KHRC and reported malpractices to relevant government bodies.

Like many Kenyans Chacha previously feared elections as they have always resulted in violence. Elections have seen politicians use ethnicity to mobilize votes which has whipped up tensions that have resulting in cross-community violence. The highly contested 2007 general elections and the disputed Presidential results led to 1,100 people killed, thousands injured, at least 40,000 incidents of sexual and gender-based violence and over 600,000 being displaced.

Lack of oversight of elections has led to violence, threats of violence (including Gender-based violence), militias and criminal gangs against all persons. It also led to use of hate speech and unsavoury language in electoral campaigns; misuse of public resources by those in power to their unfair advantage in the electoral contest; and voter buying, voter bribery, unwarranted assisted voting, voter intimidation and theft of IDs. Marginalized groups such as women, persons with disabilities, youth and other minorities also saw discrimination during these processes.

History has a role to play in the reasons as to why stakes are high in an election win for many Kenyans. Political leadership in Kenya is a space for the elite ethnic groups favoured by or who collaborated with the colonial administration. This system is not inclusive with successive Governments leaving certain ethnic groups out of politics. Marginalised ethnic groups lack the numbers to win an election in a country where voting is primarily along ethnic lines. This has led some to question whether the First Past The Post (FPTP) electoral system is suitable for Kenya and whether a proportional representation system would foster better representation and inclusivity.

Marginalised ethnic groups also have a sense that successive elections have been stolen leading to a sense of disenfranchisement and sentiments that they should disengage from political participation. Resource allocation has mirrored allocation of political power so that Counties that do not have senior politicians representing their interests lack developmental initiatives such as infrastructure, social amenities and employment opportunities.

Positively, the Electoral Monitoring and Reform project, supported by the Danish Embassy through the Drivers of Accountability Programme (DAP), resulted in a paradigm shift from monitoring elections only on the Election Day to monitoring based on the electoral cycle; from pre –election, Election Day and Post- Election. A human rights based approach is used in this process. Arguably, one of the most important aspects of this project was working with existing human rights networks on the ground and individuals such as Chacha meaning that the project made a significant and sustainable contribution to strengthening human rights awareness among the communities.

Nationally, KHRC analyzed the reports it received from community-based monitors across the country and presented findings and recommendations in a report titled 'Democratic Paradox: A Report of Kenya's 2013 General Elections.' The IEBC have lived up to their commitment to act on these recommendations by implementing some of the suggestions made by the KHRC. Effective registration of voters in the diaspora was one of the recommendations made by KHRC. Notably, the IEBC in February, 2015 launched an online mapping tool that will see them effectively register voters in the diaspora. Additionally, in March 2015 the IEBC launched a school project on voter education that seeks to nurture democracy in young Kenyans. Development of strategies for school-based voter Education targeting primary and secondary schools as a way of inculcating democratic values in both pupils and students was another recommendation made by KHRC.

The structures in place to enable civil society, the IEBC, political parties, the office of the registrar of political parties and other electoral stakeholders to collaborate in monitoring elections have been reinforced through the creation of the election Technical Working Group (TWG) which is co-chaired by KHRC and the Institute for Education in Democracy (IED). Additionally, KHRC and IED created a WhatsApp group which enables CSOs, election monitors, IEBC commissioners and senior management to engage on key emerging electoral issues in real time. This should make the challenge of a lack of civilian oversite of elections a thing of the past.

However, electoral related violence is an issue across several African countries with many states suffering the ethnic polarization that Colonialism seeded through its divide and rule policies. Subsequent political despots have enhanced this through the manipulation of ethnic identity for political gain. The ‘Big Man’ approach to politics remains, where a leader, promises ‘development’ and ‘jobs’ to his ethnic homeland if voted into power, instilling a commitment to ethnic voting even though the majority of poor people from all ethnicities do not benefit whoever the leader.

There are numerous African leaders who have sought to undermine democracy in a desperate bid to cling to power, for example, Burundi in 2015. Thus, regionally, KHRC’s electoral governance assessment framework has been utilized in South Africa, Botswana, Malawi and Zambia. KHRC has raised the potential for an African framework on election monitoring at the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) where there has been significant interest in developing such a framework.

In recognition of its established track-record on electoral governance matters, KHRC in 2014 was admitted as a member to the Global Network of Domestic Election Monitoring (GNDEM). This membership will enhance its regional and international advocacy on electoral governance. This is because it avails a global platform to engage with likeminded organizations on topical electoral governance issues. It will also share reports and other resources. Through this, people outside of Africa can benefit from the use of this practical election process monitoring tool.

Elections in Africa can be reformed to become inclusive, credible and peaceful processes that can lead to better governance across the continent. It is through people like Chacha, that this ambitious dream shall be realized

KHRC participates at the Law Society Awareness Week

The KHRC participation included offering free legal advice to the public as well as distributing advocacy reports to help empower and educate Kenyans with knowledge in when in search for redress and justice.

“The public needs Legal assistance, to meaningfully engage and effectively make use of the legal system and to enjoy the full breadth and freshness of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 which guarantees the various rights to a fair trial.” Said Justice Mohammed Ibrahim.

KHRC celebrates Kenya's Heroes and Heroines

The highlight of the event was different age generations sharing symbolic mementos with younger generations. The 90s & 80s shared a picture of the memorial and the flag of Kenya to the 70S & 60S generation. The flag symbolized the fight for self-determination and the picture captured the reparation gesture that the memorial stands for.

The 70s & 60s shared the Constitution of Kenya, with the 50s&40s; the Katiba symbolized the struggle for the second liberation and for the realization multipartism. The 50s&40s shared four reports i.e. Krigler, TJRC, CIPEV and Ndungu’s report on Historical Land Injustices. These are some of the important documents that detail what bedevils Kenya as a country yet their recommendations are yet to be implemented.

The 30s & 20s shared a whistle and a picture of a flash disk with the below 20s generation. These mementos signified the new space of online advocacy platforms and the culture of whistle blowing.

Apart from the presence of the Maumau War Veterans Association, other liberation movements like Dini Ya Musambwa, Koitalel Arap Samoei and Mekatilili Wa Menza also attended the event. There was also representation from the civil society, donors and representatives from five universities and twenty five schools both primary and secondary.

George Kegoro speaks at the Kenya: Governance Assessment report launch by Freedom House

Other panelists at the launch included; Commissioner Jedidah Wakonyo from the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, Dr.Willy Mutunga former chief justice of Kenya and Kwame Owino the Chief Executive Officer, Institute of Economic Affairs and John Tuta, Head of legal at The Attorney Genral's Office.

KHRC was among the commissions that validated the report. The report assesses Kenya’s progress towards improving government accountability, promoting civic liberties, human rights, rule of law and transparency over a three year period, between January 2013 and July 2016.

The report is divided into four components; Civic Space, Security and Human Rights, Rule of Law and independence of the Judiciary and Corruption and accountability.

“Closing of civic space is an attempt by the state to disrupt citizen power” stated George Kegoro

To access the full report click here

To view more photos from the launch click here

UN/African Union: Reject ICC Withdrawal

Security Council Meeting With AU

(New York, September 22, 2016) – The African Union (AU), in advance of a meeting with the United Nations Security Council on September 23, 2016, should end consideration of a call for mass withdrawal of its members from the International Criminal Court (ICC), a group of African nongovernmental organizations and international groups with a presence in Africa said today.

In January, the AU decided to mandate its Open-Ended Committee on the ICC to develop a “comprehensive strategy” that includes withdrawal from the ICC. The committee met on April 11, and identified three conditions that it said should be met for the AU to avoid calling for withdrawal. These included a demand for immunity for sitting heads of state and other senior officials from prosecution before the ICC.

“AU efforts to undermine the only permanent criminal court for victims of atrocities are fundamentally at odds with the AU’s rejection of impunity, and with its decision to make 2016 as the AU’s year of human rights,” said Stella Ndirangu of the Kenya section of International Commission of Jurists. “The AU’s commitment to justice cannot be reconciled with protecting African and other leaders from accountability for mass atrocities before the ICC.”

Article 4 of the Constitutive Act of the AU expressly rejects and condemns impunity. The AU has also identified justice as one of its “shared values,” and 2016 as the “African Year of Human Rights with Particular Focus on the Rights of Women.”

Some African ICC members are taking important steps to limit impunity, the organizations said. At the AU’s summit in Kigali from July 10 to 18, several African countries – Botswana, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Senegal, and Tunisia – pushed back against a potential call by the African Union for a mass exit of African countries from the International Criminal Court. Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Senegal alsoentered reservations to the AU decision that was adopted at the summit to continue its consideration of ICC withdrawal.

In the period before the summit, 21 international and African nongovernmental organizations released avideo featuring 12 African activists on the importance of the ICC and the need for African governments to support the court. The video, and a shortened version of it, have attracted more than 80,000 views on social media.

Withdrawal from the ICC is a decision to be made by individual countries and cannot be carried out by the AU. At the same time, a call from the AU for countries to withdraw or consider withdrawal would make it more difficult politically for African countries to show support for the court.

“The ICC remains the crucial court of last resort,” said Timothy Mtambo of Malawi’s Center for Human Rights and Rehabilitation. “The AU should work to strengthen and support the ICC, not urge its members to quit the institution.”

The work of the Open-Ended Committee on the ICC is the latest development in a backlash against the ICC by some African leaders, focused on charges that the ICC is unfairly targeting Africa. The backlash first surged in the wake of the 2009 ICC arrest warrant for President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan, on charges of serious crimes committed in Darfur. It reached a new level of intensity in 2013, when then ICC suspects Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto were elected president and deputy president of Kenya, respectively.

Six out of the nine African situations under ICC investigation came about as a result of requests or grants of jurisdictions by African governments – Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Uganda, and two requests from the Central African Republic. In January, the ICC prosecutor opened the court’s first investigation outside Africa, in Georgia, and it is conducting several preliminary examinations of situations outside Africa. They include Afghanistan, Colombia, Palestine, and alleged crimes attributed to the armed forces of the United Kingdom deployed in Iraq.

At the same time, some powerful countries – including China, Russia, and the United States, all permanent UN Security Council members – and their allies have been able to avoid the reach of international justice. They have been able to do that by not joining the ICC and because they have a veto on the UN Security Council, which can refer situations to the court. The organizations encouraged the AU to raise these concerns during its meeting with the UN Security Council.

The three conditions the AU’s Open-Ended Committee on the ICC set at its April 11 meeting for remaining in the ICC are:

- Immunity under the ICC’s Rome Statute for sitting heads of state and heads of government and senior government officials;

- Intervention of the ICC in cases involving African states only after those cases have been submitted to the AU or AU judicial institutions; and

- Reduction in the powers of the ICC prosecutor.

Blanket immunity for sitting heads of state has never been available before international criminal courts dealing with crimes under international law. No international tribunal – from the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, to the International Criminal Tribunals for the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, to the ICC – has allowed immunity on the basis of official position.

The AU in 2014 adopted a protocol to give its regional court authority to prosecute grave crimes, also while granting immunity for sitting heads of states and other senior government officials. That protocol, which needs 15 ratifications before coming into force, has yet to be ratified by any country.

Kenya has played a leading role in mobilizing AU attacks on the ICC since 2013. On September 19, the ICC issued a finding of non-cooperation by Kenya in the now-withdrawn case against Kenyatta to the ICC’s Assembly of States Parties. The charges in the case against William Ruto, Kenya’s deputy president, were vacated for lack of evidence in April.

The decision is the first ICC finding of non-cooperation related to the failure of an ICC member country to provide assistance to the prosecution’s investigations.

For more on views of independent organizations on backlash against the ICC in Africa, please visit:

http://www.southernafricalitigationcentre.org/2015/07/02/101-civil-society-organisations-support-salcs-efforts-to-arrest-bashir/

http://www.icj-kenya.org/index.php/media-centre/press-releases/7-news/647-africa-civil-society-recommendations-to-13-session-of-the-assembly-of-state-parties-to-the-rome-statute

https://www.defenddefenders.org/2016/07/african-union-activists-challenge-attacks-on-icc/

For more information, please contact:

In Abuja, for LEDAP-Legal Defence & Assistance Project, Chino Edmund Obiagwu (English): +234-0703-000-0014; or +234-012-802-009; or +234-0803-691-3264 (mobile); or obiagwu@ledapnigeria.org

In Freetown, for Center for Accountability and the Rule of Law-Sierra Leone, Ibrahim Tommy (English): +232-76-365-499; or ibrahim.tommy@gmail.com

In Johannesburg, for Southern Africa Litigation Centre, Angela Mudukuti (English): +27-767-623-869; orAngelaM@salc.org.za

In Lilongwe, for Center for Human Rights and Rehabilitation, Timothy Mtambo (English): +265-992-166-191; or mtambot@chrrmw.org

In Nairobi, for Kenya section of the International Commission of Jurists, Stella Ndirangu (English): +254-7222-336-399; or stella.ndirangu@icj-kenya.org

In New York, for Human Rights Watch, Elise Keppler (English): +1-917-687-8576 (mobile); +1-212-216-1249 (office); or kepplee@hrw.org. Twitter: @EliseKeppler

In New York, for Coalition for the ICC, Steve Lamony (English): +1-646-465-8514; orlamony@coalitionfortheicc.org

The following organizations that are active in an informal group that promotes support for serious crimes endorsed this news release:

Affirmative Action Initiative for Women (Nigeria)

African Center for Justice and Peace Studies (Uganda)

Africa Legal Aid

Center for Accountability and Rule of Law – Sierra Leone

Children Education Society (Tanzania)

Civil Resource Development and Documentation Centre (Nigeria)

Coalition for the ICC

Coalition of Eastern NGOs (Nigeria)

Federation Internationale des Droits de l’Homme (FIDH)

Foundation for Human Rights Initiative (Uganda)

Ghana Center for Democratic Development

DefendDefenders-East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Network

Human Rights Watch

International Crime in Africa Program, Institute for Security Studies

International Commission of Jurists (Geneva/Johannesburg)

International Commission of Jurists-Kenya

Kenya Human Rights Commission

Kenyans for Peace with Truth and Justice

Legal Defense and Assistance Project (Nigeria)

Malawi Center for Human Rights and Rehabilitation

Kenya Human Rights Commission

NamRights (Namibia)

Nigerian Coalition for the International Criminal Court

Rights and Rice Foundation of Liberia

Southern Africa Litigation Centre

Petition to the President of the Republic of Kenya to end enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions by the Police

His Excellency, Uhuru Kenyatta

C.G.H. President and

Commander in Chief of The Defence Forces of The Republic of Kenya

Harambee House

Harambee Avenue

P O Box 62345- 00200

Nairobi, Kenya

July 4, 2016

HE Uhuru Kenyatta,

Petition to the President of the Republic of Kenya to end enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions by the National Police Service and provide justice for families of the disappeared and murdered

Loading...

Loading...

Press Release on Killings of Lawyer and Two Men

Kenyan authorities must urgently investigate the killing last week of three men, including a human rights lawyer, and ensure that those found responsible are held to account in fair trials, 29 Kenyan and international human rights organizations said today. Human rights activists will today hold demonstrations in Nairobi and other parts of Kenya today to protest the heinous killings.

Loading...

Loading...