Going through the motions: Verra’s review of sexual abuse at Kasigau

On 6 November 2023, the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) and the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) published a report documenting serious allegations of sexual harassment and abuse at the Kasigau carbon offset project in Kenya, which is run by the US-based company, Wildlife Works Carbon (‘Wildlife Works’).

In response, the standard-setting body, Verra, suspended the project and announced it would pursue an investigation into the issues. Verra, which describes itself as managing “the world’s leading voluntary carbon markets program”, is the main standard-setting body for carbon offset credits in the voluntary carbon market, particularly for forest-based projects. Verra’s certification of projects such as Kasigau is the basis on which customers – usually major multinational companies – buy carbon credits. On 1 February 2024, Verra published the outcome of its review of the Kasigau project.

Verra concluded that Wildlife Works “has demonstrated that it is taking the actions required to address the alleged harm and to mitigate the risk of future harm.” As a result, Verra lifted the project’s suspension and restored Wildlife Works’ ability to generate carbon credits from Kasigau.

Below we assess Verra’s review in more detail. KHRC and SOMO shared our concerns about the review with Verra and received a response from the organisation on 22 March.

A flawed review with harmful omissions

Verra’s review covers four issues (which it terms ‘findings’): namely, sexual offences; inadequate mechanisms for reporting sexual offenses; other negative community impacts; and improper employment practices. In each section, Verra sets out the allegations, the requirements of the various carbon offset standards that are applied to the Kasigau project, and the response of the project developer - Wildlife Works.

Finding 1: Sexual Offences

In its review of Kasigau, Verra claims that it “took into account the full SOMO/KHRC Report” However, the Verra Review Findings Report fails to address many of the abuses identified in our research. Moreover, it appears to be based substantially on an internal investigation carried out by a law firm commissioned by Wildlife Works and on information provided by Wildlife Works to Verra, even though it was the company’s failures that were being investigated.

Following the law firm’s investigation, Wildlife Works announced that it had terminated two members of staff, one for gross misconduct involving a breach of company policy on sexual harassment, and another – the Human Resources (HR) Manager – for creating a “culture of fear” that prevented reporting of sexual misconduct.

While these actions are important, KHRC and SOMO have expressed concern about the limitations of the Wildlife Works’ investigation process. One key concern is that the company has claimed that our report “attempts to indicate the widespread nature of this problem, yet in their letter to us [Wildlife Works] they identified one perpetrator as responsible for the specific sexual harassment allegations, and one department as the place where all these allegations occurred; and A&K’s [the law firm hired by Wildlife Works] investigation also found that was the case.”

This statement by Wildlife Works is false, and in a public response on 9 November, 2023, KHRC and SOMO formally challenged it, making it clear that we had identified several alleged perpetrators of sexual abuse. The letter that Wildlife Works refers to in the above quote was sent to them on 4 August 2023, before the report was published. The following are direct quotes from that letter with the redaction of one individual’s name and title:

“Our investigations at Kasigau have revealed serious allegations of sexual exploitation, harassment, sexual assault, and attempted rape of women by senior employees of Wildlife Works (WLWs) and by rangers employed by Wildlife Works. Women interviewed named some of the individuals who extorted sex based on the power of their position and/or the inability of women to prevent the abuse.”

“Over the course of our investigation [name redacted] was named repeatedly. For the avoidance of any confusion, this individual was also sometimes referred to as the [title redacted], but always as [name redacted]. Other individuals, including office staff and rangers, were named also as being involved in sexual harassment and/or assault of women. These names are not shared here due to the need to protect those who gave testimony.”

This letter – and the report itself – could not be plainer about the scope of the allegations we documented. KHRC and SOMO drew Verra’s attention to the incorrect claims made by Wildlife Works about the number of alleged perpetrators of sexual harassment and abuse. However, Verra did not respond on this point. Instead, in a letter dated 22 March 2024, Verra stated that the investigation commissioned by Wildlife Works “was not able to corroborate further instances of harassment or abuse”. This response is disingenuous. If the Wildlife Works investigation was based on the false premise that the sexual abuse was limited to one person and one department, as it appears to have been, this would clearly affect its findings.

Moreover, if Verra “took into account the full SOMO/KHRC Report” as it claims, then it should be aware that one section of that report covers the Wildlife Works internal investigation, and raises several critical issues. These include that the lawyers’ choice of people for interview was based on unknown criteria; that many of the people who provided testimony to our researchers were not selected for interview; and that the investigation process was conducted in a location that was used by one of the alleged perpetrators to coerce women into sex, suggesting a lack of awareness of basic good practice in interviewing victims of sexual abuse. There was, based on our research, no apparent way for people to come forward and volunteer testimony. Yet, this is precisely what should have been done, offering people the chance to speak to the lawyers in places of their choice, where their privacy and dignity would be guaranteed.

Verra’s Review report fails to engage with any of these issues. As a result, many allegations of abuse, documented by KHRC and SOMO, are swept away on the basis of an investigation whose weaknesses Verra appears to disregard. For example, multiple testimonies referred to the sexual misconduct of one individual, including from two women who reported that this man had assaulted them, and rangers who told us that they witnessed him assaulting a woman from the community. This man, we understand, is still employed by Wildlife Works.

Finding 2: Inadequate mechanisms for reporting sexual offenses

Verra notes that the KHRC/SOMO report “alleged that the project proponent impeded attempts, and imposed barriers, to report the offenses referred to above.” As noted earlier, during its internal investigation, Wildlife Works found that its HR manager at Kasigau had “created a culture of fear and intimidation that, according to interviewed personnel, prevented reporting of sexual harassment incidents.” Wildlife Works provided additional detail to Verra stating that “it was determined that the former HR Manager subverted our grievance mechanism, by stopping committee meetings, removing some suggestion boxes and creating an atmosphere in which reporting was discouraged”.

Verra appears to accept this information without any further inquiry. It does not ask why no other manager or senior person was aware of the HR manager’s actions. Nor why no staff were able to raise his conduct with anyone else at the company.

Instead, in its review report, Verra reproduces, without comment, Wildlife Works’ statement that “[t]he verification process shows that the grievance mechanism is functional.” The ‘verification process’ to which Wildlife Works refers is the auditing process. This is the same process which repeatedly, over years, failed to identify the sexual harassment and abuse and failed to identify how the grievance process was being subverted by the HR manager.

Wildlife Works has acknowledged that its grievance process was, indeed, flawed, stating on 5 November 2023, that:

“It is painfully clear to us now that we had gaps in our grievance process specific to sexual harassment issues, which must be treated differently and we are committed to fixing this issue.”

This somewhat baffling juxtaposition of Wildlife Works’ (earlier) admissions — that its HR manager “subverted our grievance mechanism” and “created a culture of fear”, — with Verra’s willingness to accept Wildlife Works’ claim that the grievance mechanism at Kasigau “is functional”, underscores the serious deficiencies in Verra’s review. Based on Verra’s review, the removal of the HR manager is deemed sufficient, without any deeper interrogation of how serious abuses were allowed to persist for years.

We asked Verra how it could accept the company’s statement that its grievance mechanism is ‘functional’ when, as clearly documented in the KHRC/SOMO report, and self-evident in this case, this mechanism prevented reporting of abuse. Verra did not provide any explanation.

For the women who were unable to report abuse through this ‘grievance’ process, Verra’s inadequate investigation adds insult to serious injury. Moreover, it suggests a level of complacency on the part of Verra towards abuse and failures that should raise red flags for customers of its products.

Finding 3: Other negative community impacts

Under this heading, Verra states that the KHRC/SOMO report, “alleged that activities linked to the Projects had negative community impacts other than those referred to in the other findings in this report, including inadequate gender sensitivity in stakeholder engagement and the limitation of fuelwood collection without providing alternatives.” (emphasis added)

The conduct Verra appears to refer to was documented in the KHRC/SOMO report as follows:

- “Women we interviewed described several recent incidents when, as they searched for and collected firewood, Wildlife Works rangers spotted them and told them to stop… On each of these occasions, the rangers subjected the women to hours of humiliation and abuse, forcing them to kneel on the ground for three hours or longer.”

- “Several women recalled how rangers had hurled explicitly sexualised insults and threats at them. In one instance, a ranger had ordered a woman to “take off your clothes… and f*** me.”

- “According to the woman, one of the rangers “held her hand” as he forced her to kneel down. Then, “when I looked up, he had exposed [his erect penis]” and “was ready to assault me”. The only reason he did not do so, she believed, was that one of his colleagues recognised her and told the assailant to stop, apparently fearing that their connection could lead to trouble.”

- “These rangers [male and female rangers interviewed] had either witnessed how certain rangers abused women or heard stories about such aggression. One of them noted that “people in the community fear the rangers” but they “don’t feel safe to go to the head office to report violent behaviour”.

- “A female ranger recalled an incident where a male colleague, who seemed to mistakenly believe he was alone with his victim, attempted to assault a community woman he found grazing her livestock near the village of Mwagwede. The ranger recalled intervening to prevent the assault and escorting the woman home and speaking to her family.”

- “In another incident, a female ranger recalled that a woman from a nearby village came to the office to report how the same ranger referred to in the incident above had assaulted her. However, as far as she knows the senior male staff member to whom she reported the attack – a ranger who is widely identified in our interviews as a key perpetrator – did not act on her report."

The above testimonies cannot be reduced to “inadequate gender sensitivity”. The testimonies also contradict Wildlife Works’ claim that KHRC/SOMO identified only one perpetrator (see Finding 1 of Verra’s review described above).

In its response to Verra on this issue, Wildlife Works focused on community members gathering firewood but did not address the reported ill-treatment and abuse. The claim made by Wildlife Works to Verra that “the independent investigation [assumed to mean the investigation carried out by the law firm hired by Wildlife Works, referred to above] found that the Project's community rangers are well aware that any mistreatment of community members is grounds for immediate dismissal” appears disingenuous. This statement suggests that Wildlife Works has not investigated allegations of ill-treatment by rangers, but only examined whether rangers knew that ill-treatment, if identified, would lead to dismissal. How does the awareness of rangers about what constitutes a firing offence (if it is found to have happened) have any bearing on the reality women experience or on accountability for abuse? Verra should have, at the very least, questioned such a statement by Wildlife Works. There is, however, no evidence that they did.

Furthermore, Verra’s review makes no reference to concerns, documented in the KHRC/SOMO report, that the conduct of some Wildlife Works staff has increased the risk of HIV infection in the community. Given the potentially severe health impacts of these allegations, they should have been part of Verra’s review.

In addition to the many serious concerns and omissions raised above, Verra’s review also fails to address Wildlife Works’ responsibility to provide meaningful remedy to all individuals affected by abuse. This company bears responsibility for harms done to people coerced into sexual relations with men working for the company. The follow-up actions reported by Wildlife Works to Verra, and accepted by Verra, do not include support for anyone whose health may have been harmed, nor other elements of the right to effective remedy, such as compensation for victims.

There is no suggestion in Verra’s review that the victims of abuse are relevant, let alone central, to any meaningful investigation into allegations of sexual harassment and abuse. The information presented in Verra’s report is based primarily on accounts by the same company that allowed these abuses to persist for years. Nor is there any suggestion that Verra has taken care to ensure that what it is told by Wildlife Works is accurate.

Verra’s reliance on auditing: the illusion of oversight

Verra’s certification of the Kasigau project is based on audits. Auditors assess carbon offset projects against Verra’s standards and provide reports to Verra. In its review of Kasigau, Verra does not reflect on how the auditors who visited Kasigau over the years failed to identify the allegations of abuse, or at least failed to report them. Nor does Verra’s review engage with testimony by an auditor, quoted in the KHRC/SOMO report, whose experiences at Kasigau made them suspect Wildlife Works had coached employees on what they were allowed to tell auditors. Verra has failed to use its leverage to bring real accountability to Kasigau, to ensure women are protected from abuse.

On the contrary, Verra states that it will rely on audits to verify Wildlife Works’ compliance with Verra’s standards going forward. Thus, the tools that manifestly failed to identify serious abuses are to be relied upon, once again.

Conflicts of interest at the heart of the carbon certification system

There are fundamental conflicts of interests at the heart of the carbon offsetting system. This may go a long way to explain why abuses at Kasigau went undetected for so long. This might also explain why Verra’s review failed to engage victims, while accepting the input of the company whose project it purports to oversee for the purpose of certification.

The auditing and certification system relies on actors with clear financial interests in a system that is being promoted as being good for the climate and communities. Auditors are, usually, companies. They are hired by project developers and are therefore auditing entities that are their clients. Based on KHRC and SOMO’s review of audits done on Kasigau, Verra appears to apply minimal scrutiny to audit reports before certifying projects. Once certified, a project can generate, and sell, carbon credits. The system works, for these actors. But at Kasigau, the system manifestly failed women employed by Wildlife Works and, based on the research of KHRC and SOMO, also individuals in the wider community.

Standard-setting organisations such as Verra are not insulated from commercial pressures. They can only survive if their self-regulated standards and verification processes are accepted by those who sell and by those who buy the carbon credits. None of these actors want news of abuses that would tarnish their reputation and businesses.

Communities, on the other hand, face being told that reports of abuse can lead to loss of benefits if the project is suspended, which can be read as a choice to accept abuse or lose benefits. No community should have to make this choice.

The illusion of accountability

Verra’s investigation into the serious abuses at Kasigau lacks credibility. It presents a facsimile of a review, but interrogates almost nothing.

In any understanding of due diligence and adequate response to allegations of serious abuse, relying substantially on the company’s input is inadequate. Yet, this is the core of Verra’s ‘findings’ and review outcomes. While Verra claims to have read other materials that provide further evidence on the case, there is little indication of this in its review.

Verra and the system it upholds are designed to protect and enable the industry at almost any cost. For all the standards and tools, the focus is on ensuring that carbon offset projects can continue to operate, and that the offset industry is protected. Such a system is not only open to abuse, it is clear from many reports, including but not limited to our own, that abuse in this system is widespread and that ignoring or minimising the harms is almost always the order of the day.

Based on its review of Kasigau, Verra appears to be unaware that it presides over the very system that enabled serious sexual abuse to go undetected for so long, and concludes its review by proposing to rely on the same wholly unfit tools to assess Kasigau going forward.

The Kasigau review process gives the carbon offset market an illusion of accountability. By doing so, it compounds rather than remedies the abuses.

Greenlighting abuse

The Kasigau Corridor REDD + Project in Kenya is a high-profile carbon offsetting project that claims to ‘avoid’ emissions by protecting forests. When ‘Ernst Wood’ (a pseudonym)[1] arrived at Kasigau, his task was clear: to evaluate whether the project, which is run by US-based company Wildlife Works Carbon (Wildlife Works), met the environmental and social criteria needed to maintain its ethical certifications.

Social and environmental auditors such as Ernst are rarely mentioned in the debate around forest-based offsetting schemes, yet the carbon credit market could not exist without them. That’s because many buyers of such carbon credits – often big polluters, such as fossil fuel companies and airlines – rely on ethical certifications as evidence that the offsetting projects on which these credits are based have real social and environmental benefits. Certificates give credibility to the impact claims that businesses such as Wildlife Works make about their forest protection or tree planting projects, and can boost the green credentials of their customers.

At the time of Ernst’s visit, Wildlife Works boasted not one but two certificates: the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards (CCB), both issued and supervised by the Washington-DC-based organisation Verra. The VCS is, in theory, supposed to confirm whether offset schemes plant or save as many trees as they purport to do. The main promise of the more expansive and community-focused CCB is that offsetting projects carrying its label deliver positive socioeconomic outcomes, such as income generation opportunities for local people and greater gender equality.

Audits are the main tool used by carbon certification schemes like Verra to monitor the environmental, social, and human rights impacts of offsetting projects. Wildlife Works has long held up its CCB label as proof that its operations at Kasigau go well beyond basic social safeguards, by ‘empowering’ the local community – especially women – through jobs and various development initiatives, known as ‘co-benefits’. Many of its customers have repeated this claim, with Netflix going so far as to make and promote a short film about the Kasigau project. By emphasising how Wildlife Works supports women’s groups and employs female rangers – an occupation traditionally reserved for men – the film depicts Kasigau as an essentially feminist project that’s entirely beneficial for local people.

Even international development organisations, such as the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), have held up Kasigau as a model of how to wed climate goals with community benefits.[2]

In 2023, an investigation into Kasigau by the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) and the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) showed that Ernst’s concerns were well founded. Drawing on interviews with over 30 employees and community members, both victims and witnesses, KHRC and SOMO documented multiple allegations of predatory men within Wildlife Works who had exploited positions of power to sexually assault, harass, and extort sex from female staff and mistreated vulnerable women in the wider community. According to multiple sources, the abuses had been going on for a decade.

A decade of auditing failures

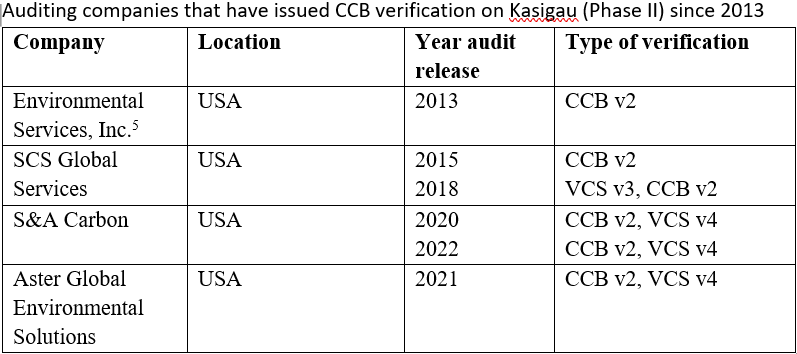

Ernst was not the only auditor to review Kasigau while egregious abuses were taking place. Between 2013 and 2022, four US-based auditing firms sent teams to the project site, with each of them reportedly interviewing dozens of employees and community members on topics such as working conditions, rights, and community impacts (see table). None of them reported finding any evidence of sexual harassment or abuse.

Yet, as community members told KHRC and SOMO, it was an open secret among employees and the wider community that, in the words of one interviewee, women were “treated as sex objects” at Wildlife Works, and that the perpetrators got away with it by “intimidat[ing] everybody”.

Instead, the auditors’ findings were reassuring and flattering towards Wildlife Works’ culture and project management. They found that the project had “overwhelmingly … positive impacts to the local communities”,[6] was “highly unlikely to result in any net negative impacts on local stakeholders”,[7] and was committed to “equal opportunity employment”.[8] “In conversations with staff,” one audit report noted, “it was learned that no negative comments or grievances were ever received.”[9]

The collective failure of these auditors is shocking but not surprising. This is because the auditing system – a largely unregulated web of private companies that compete for contracts from offset project developers – is set up in such a way that it’s nearly impossible for auditors to meaningfully investigate and report on abuses. What emerges as a result is a ‘paper reality’ that is at best incomplete, and at worst a fiction, replete with misleading reassurances around the wellbeing of some of the world’s most marginalised communities.

The reasons the auditing system failed so spectacularly at Kasigau appear inherent in the system. These include: the power imbalance between local people (both employees and other members of communities) and carbon project developers; the limitations placed on auditors, restricting the scope of their reviews; the auditors’ bias in favour of the project developers who are their clients; and the conflict of interest in the relationship between auditors and project developers. We consider each of these reasons in turn below.

SOMO wrote to the auditing companies listed in the table above. Only SCS Global responded, telling us that its assessment team had not heard or received any “allegations about sexual harassment or assault”.[10]

The power imbalance

Ernst’s suspicion that things were not as they seemed was triggered by his discussions and informal chats with Wildlife Works’ local staff. During these conversations, Ernst heard disturbing stories of what women at the company were put through by more senior male colleagues. For example, he learned about an incident where a female employee asked for an advance on her salary and was told that “she had to ‘earn it’ by providing sexual favours”. In another incident, a woman had allegedly been “pressured repeatedly to sleep with a more senior colleague”.

Ernst said he had tried, but failed, to get interviewees to speak about these and other problems on the record, but that staff members and especially junior staff seemed unable to speak freely. I had the impression that they had been told what to tell us and were afraid to defy these instructions. While I tried to convince them that they could share problems with me, I left those interviews feeling they were afraid to open up.

Project employees were not the only group Ernst believed to be holding back during interviews. Community members, he explained, “who benefit from project carbon revenues are less likely to share [problems], as doing so may risk the continuation of project benefits”.

As a result of these power asymmetries, and the apparent lack of trust in the audit process on the part of Ernst’s interviewees, none of his concerns made it into his audit report.

The barriers Ernst ran into during his audit shine a light on how the power imbalance between offset project developers, on the one hand, and their staff and local communities, on the other, shapes audit outcomes. In theory, the interviews used to monitor the social impacts of an offsetting project are more straightforward than the messy and discredited methods used to calculate carbon emission reductions. But in practice, local employees and communities have good reasons to keep concerns to themselves.

Staff might, for example, have been told by their boss what to tell (or not tell) the auditors, as Ernst suspected had happened at Kasigau. In other cases, auditors might conduct interviews accompanied by a manager from the project developer. Ernst, based on his experiences, believes this to be “common practice”, despite the obvious limiting effect that such managerial presence can have on the ability of staff to speak openly about problems.

Limitations placed on auditors

As Ernst also noted, audits can be manipulated, particularly if the verification system limits the scope of inquiry. SCS Global appears to agree, telling SOMO: “[A]dequate consultation with communities may require numerous engagements over a lengthier period of time than has sometimes been afforded to the validation and verification body. Indeed, some of our requests for added time are met with great resistance.”

The power asymmetries between companies like Wildlife Works and communities, then, combine with the limitations the system places on auditors, in ways that fundamentally disadvantage workers and communities. Companies have a responsibility and, increasingly, a legal obligation, to account for and report on the impact of their activities on people and the environment. While some see social and environmental audits as a tool to deliver on this responsibility, the flaws of such processes have been repeatedly exposed by civil society organisations.

Bias in favour of clients

In 2020, one or more community members living around Kasigau chose to remain anonymous when they tried to report concerns to S&A Carbon, which audited Kasigau that year. These concerns related to the allegedly “unfair hiring practices” of Wildlife Works’ Human Resources Department. According to S&A’s audit report, the written complaint called for the “removal” of Wildlife Works’ HR Manager at Kasigau and for people “to be treated with respect and dignity”.[11] Although the audit report is vague on the exact content of the complaint, it suggests it also raised unfair termination practices as an issue.[12]

More concerningly, S&A accepted, seemingly without any attempt at verification, Wildlife Works’ assertion that the complaint was “based in personal conflict between the individual(s) and the project and that therefore the discrimination accusations have no merit”.[13] The auditors reported that Wildlife Works “believes they know the identity or at least the family who raised the comment” and “is confident that the letter originated from [location redacted by SOMO]”.[14] To respond to the issue, the auditors go on to explain, Wildlife Works planned to hold community meetings in the location it assumed the grievance stemmed from. [15]

One obvious problem with S&A’s handling of this complaint is how its apparent bias towards Wildlife Works’ version of events led it to largely disregard the concerns of one or more community members. Equally troubling is how S&A chose to include in its public report a presumed characteristic of the anonymous complainant(s) – the name of their location – that could very well lead to identification. It is not difficult to see how S&A’s handling of this complaint could have a chilling effect on employees or other members of the community, who might think twice before reporting concerns.

One year later, Aster Global visited Kasigau for Wildlife Works’ 2021 audit. The auditors, who were aware of the anonymous complaint filed the previous year, should have had additional cause for concern around Wildlife Works’ hiring and termination practices. Three similar complaints had been made through Wildlife Works’ grievance system.[16] Yet despite this additional evidence of problems related to human resources practices, Aster Global’s audit report does not mention the new complaints, and there is no evidence the auditors investigated the issues. [17]

The apparent failure to investigate such signals about potential problems more deeply may help explain why a decade of auditing failed to uncover any of the abuses that KHRC and SOMO have exposed.

This seeming tendency of auditors to give clients the benefit of the doubt is no anomaly in the carbon offsetting world. Recent research by the Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley, has shown such auditors’ bias to be pervasive in the industry. The Berkeley researchers reviewed project descriptions and audit reports on Kasigau and 17 other forest-based offsetting projects. They found that safeguarding compliance appears to be “systematically rubber-stamped despite evidence of noncompliance”.[18]

“Time and again,” the Berkeley researchers explain, “projects received positive verifications despite woefully inadequate consultation, evidence of contested land claims, and even violent evictions.” Auditors accept problematic community engagement practices and consistently give their clients “the benefit of the doubt”, “while doing minimal due diligence” on their claims.

Conflict of interest

The commercial relationships between auditors and the developers that run carbon offsetting projects have a profound impact on how auditors engage with employees and communities, and interpret the testimonies given to them. Like offsetting more broadly, auditing is a profit-driven industry, where firms compete for contracts from companies such as Wildlife Works. Auditors receive payment for their services from the very same company whose behaviour and impacts they are supposed to scrutinise.

As an auditor, asking tough questions on community relations, and digging deeper than your rivals on issues like working conditions, is therefore unlikely to make you popular with a clientele whose ability to sell credits hinges on having positive outcomes highlighted by their audit reports. This creates an inherent conflict of interest at the heart of the audit system, which can undermine the confidence that local staff and community members have in the auditors in whom they are expected to confide.

This does not mean that auditors deliberately ignore problems, but it presents them with an incentive to give clients the benefit of the doubt. As Ernst explained, the market reality imposes pressures on auditors that “limit the level of investigation” they can apply.

Conclusion

Sexual harassment and abuse, and a culture of fear created by a HR manager, were a reality at Kasigau. Audit firms repeatedly failed to identify or report on this reality. These firms operate within a system and to a standard that made it seem impossible for at least one auditor to raise their serious concerns about women’s safety at Kasigau.

Ernst Wood spoke to KHRC and SOMO because he worries that the people who end up paying the price for the structural shortcomings of the auditing system are those who are often already marginalised. They want he wants to see the damage done by the system repaired.

Individuals like Ernst play a critical role in bringing the truth to light, but it is not easy for them to do so. This is because both the carbon offsetting industry and the carbon certification industry are exactly that: industries, governed by competitive pressures, profit objectives, and private interests.

An irreconcilable and dangerous tension exists between such business pressures, on the one hand, and the rights of communities and workers on the other. And this means that even auditors such as Ernst, who are willing to ask tough questions, lack the tools and means to protect and support communities.

Research note

SOMO contacted Aster Global Solutions, SCS Global and S&A Carbon for comments on the sexual harassment and abuse at Kasigau and their failure to identify it. Only SCS Global responded.

SCS Global said:

We stand behind the audit procedures implemented during this assessment. SCS GHG audits are conducted following standard auditing operating procedures in accordance with the rules and requirements of our International Standards Organization (ISO) accreditation under the ANSI National Accreditation Board (ANAB). Above all, SCS employed the standard of care of Validation and Verification Bodies (VVBs) at the time.

As a benefit corporation, SCS is fully committed to driving positive change toward greater governmental and corporate environmental and ethical responsibility. We share your interest in preventing human rights abuses around the world.

In August 2023, SOMO raised the issue of deliberate action to mislead validation and verification bodies in a letter to Wildlife Works. We informed the company:

SOMO received testimony that, prior to auditors coming to inspect the project, Wildlife Works has instructed or coached staff on how to behave and respond. This coaching appeared to be intended to provide a partial, and therefore misleading, picture of the work conditions to the social auditors.

Wildlife Works did not respond to us on this issue.

ENDNOTES

[1] We refer to this person as 'Ernst Wood’ to protect their anonymity.

[2] Since the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) and the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) released their report on Kasigau (Offsetting Human Rights, 2023, www.somo.nl/offsetting-human-rights), UNEP has added a disclaimer to its article on Kasigau, stating that it doesn’t officially endorse individual projects; yet the article continues to uncritically repeat Wildlife Works’ claims about Kasigau’s impacts.

[3] SOMO interviewed Ernst between 10 and 20 March 2024 by phone. This article includes quotes from these conversations, as well as quotes from interviews done with Ernst in 2023 for the KHRC and SOMO report, Offsetting Human Rights.

[4] Wildlife Works Statement, Updates from the Kasigau Project, November 20, 2023, https://www.wildlifeworks.com/post/update-on-kasigau

[5] The division of Environmental Services that used to provide forestry carbon audits spun off in 2019 when their principal employees purchased this division and began operations as Aster Global https://www.asterglobal.com/about-us/

[6] S&A Carbon, Verification report for the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project phase II – the

community ranches, 2020, p. 54 https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=47114&IDKEY=kkjalskjf098234kj28098sfkjlf098098kl32lasjdflkj909j64970206

[7] Environmental Services Inc, Climate, Community, and Biodiversity Alliance Project Annual Verification Report, 2013, p. 33 https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=41997&IDKEY=j0e98hfalksuf098fnsdalfkjfoijmn4309JLKJFjlaksjfla9857913863

[8] SCS Global Services, Final CCBA Project Verification Report, 2015, p. 24, https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=42218&IDKEY=9kjalskjf098234kj28098sfkjlf098098kl32lasjdflkj909958218622

[9] Environmental Services Inc, Climate, Community, and Biodiversity Alliance Project Annual Verification Report, 2013, p. 18

[10] See ‘Research note’ below.

[11] S&A Carbon, Verification report for the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project phase II – the

community ranches, 2020, p. 16, 81-85 https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=47114&IDKEY=kkjalskjf098234kj28098sfkjlf098098kl32lasjdflkj909j64970206

[12] S&A Carbon, Verification report for the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project phase II – the

community ranches, 2020, p. 83-85 https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=47114&IDKEY=kkjalskjf098234kj28098sfkjlf098098kl32lasjdflkj909j64970206

[13] S&A Carbon, Verification report for the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project phase II – the

community ranches, 2020, p.82 https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=47114&IDKEY=kkjalskjf098234kj28098sfkjlf098098kl32lasjdflkj909j64970206

[14] S&A Carbon, Verification report for the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project phase II – the

community ranches, 2020, p.82-83 https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=47114&IDKEY=kkjalskjf098234kj28098sfkjlf098098kl32lasjdflkj909j64970206

[15] S&A Carbon, Verification report for the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project phase II – the

community ranches, 2020, p.83 https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=47114&IDKEY=kkjalskjf098234kj28098sfkjlf098098kl32lasjdflkj909j64970206

[16] This audit required the Aster Global auditors to review the anonymous complaint raised earlier. See Aster Global Environmental Solutions, The Kasigau Corridor REDD+ Project Phase II – The Community Ranches, 2021, p. 51-52, https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=59529&IDKEY=f0e98hfalksuf098fnsdalfkjfoijmn4309JLKJFjlaksjfla9k82090491. A 2021 accuracy review by Verra of an audit by Aster Global Environmental Services of the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project Phase II reveals (p.4) that of all concerns filed through the Wildlife Works grievance system in the previous year, three “were identified as rising to the level of potential dispute between the project and communities or other stakeholders, with these three involving concern over hiring or termination practices”. According to Verra’s report, which was still ‘pending’ at the time of writing, “[t]he short-term resolution identified for these [concerns] was for the community relation and HR department to organize HR employment and working procedures in the complainant's’ [sic]communities after the Covid pandemic abates”. Aster Global’s audit report does not give any details around the nature of the concerns raised through Wildlife Works’ grievance system. Aster Global Environmental Solutions, The Kasigau Corridor REDD+ Project Phase II – The Community Ranches, 2021, p. 17, https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=59529&IDKEY=f0e98hfalksuf098fnsdalfkjfoijmn4309JLKJFjlaksjfla9k82090491

[17]Aster Global Environmental Solutions, The Kasigau Corridor REDD+ Project Phase II – The Community Ranches, 2021, p. 17. https://registry.verra.org/mymodule/ProjectDoc/Project_ViewFile.asp?FileID=59528&IDKEY=f097809fdslkjf09rndasfufd098asodfjlkduf09nm23mrn87m82089112

[18] ‘Quality Assessment of REDD+ Carbon Credit Projects’ (2023) by Berkeley Carbon Trading Project (2023), p. 177- 179.

Responses to the allegations of sexual abuse at the Kasigau carbon offset project run by Wildlife Works

In November 2023, the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) and the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) exposed serious allegations of sexual harassment and abuse at the Kasigau carbon offset project, run by Wildlife Works Carbon, in Kenya.

The allegations of abuse dated back at least a decade and affected current and former employees of Wildlife Works and women living in the nearby communities. The company, which failed to identify this long-standing abuse, set up an investigation based on our reporting, and this led to the dismissal of one individual “for gross misconduct, including conduct in violation of the company’s policy against sexual harassment.”

Wildlife Works also terminated its Human Resources manager because he “created a culture of fear and intimidation that, according to interviewed personnel, prevented reporting of sexual harassment incidents.”

Wildlife Works subsequently alleged that SOMO had paid individuals to come forward with testimony. This is a baseless claim. Neither KHRC nor SOMO have ever paid people to provide information. Our organisations have a combined eighty-year record of ethical research and human rights activism.

KHRC and SOMO are unable to disclose the names of those who provided testimony to us, as we guarantee the anonymity of individuals, which is of paramount importance in research involving survivors of sexual harassment and abuse.

Protecting the victims’ identities is one of the reasons why KHRC and SOMO enjoy the trust of victims of corporate harm and abuse. When women and men come forward, they should be able to do so with their privacy and dignity protected. For this reason, we went to lengths to protect the women who came forward to tell their stories.

It is clear that the company found that the allegations documented by KHRC and SOMO were manifestly correct. However, the company has not investigated all the information provided.

Our research makes evident that allegations of sexual abuse were not confined to one perpetrator or one department. Our report and correspondence with Wildlife Works have been clear about the scope of the allegations we documented.

The decision by Verra to temporarily suspend the Kasigau project appears to have created a situation where communities believe that reports of abuse can lead to a loss of (potential) benefits.

This is consistent with the testimony given to us by an auditor of Kasigau (cited in our report) who told us that “local communities who benefit from project carbon revenues are less likely to share such issues, as doing so may risk the continuation of project benefits”.

The risk is that people are left with a choice to either live with abuse or lose benefits.

Meanwhile, at Kasigau, we understand that individuals who asked for anonymity and got it from KHRC and SOMO are being identified. This deepens our concern that a culture is emerging whereby those who suffer abuse may hear the message – do not expose abuse because the whole community may lose their benefits.

This case exposes the insidious core of the carbon offsetting industry: reporting abuse can threaten the profits of the carbon offset business. No community anywhere should have to choose between reporting abuse or losing benefits. Communities at Kasigau should not lose benefits due to a corporate failure to identify and prevent sexual harassment and abuse. Nor should any woman ever have to face the choice of silent acceptance of sexual harassment and abuse to preserve wider community benefits from a company.

https://youtu.be/Lgjvrr26iYY?si=qsfiK2NBipNl9Ty0